Giving: The Essential Teaching of the Kabbalah is a conceptual overview of the teachings of Rabbi Yehuda Lev Ashlag, author of the Sulam commentary on the Zohar, with extensive explanations and interpretations by his living student, Rabbi Avraham Mordechai Gottlieb (“with commentary and insights for living the Kabbalah”), translated into English by Aryeh Siegel. This is a book of substance because it presents in a popularized form the teachings of an authentic master of Kabbalah. As such, it is an intense and demanding book. And it is in many ways the opposite of most such popular explanations of Judaism because it is unyieldingly and uncompromisingly dedicated to explaining that a person must set aside expectations and desires of receiving and focus as completely as possible solely on giving. The fact that we are living in material bodies in a material world adulterates all absolute systems of selflessness. Thus, in practical terms Giving recommends that a person form a society of at least three people who will meet regularly to inspire each other and who will give to and support each other as lovingly and selflessly as possible. It is not through outreach programs and mitzvah campaigns but by internal change in a person that will naturally have an effect on the environment that a messianic atmosphere will be created: one in which everyone is concerned with giving to and assisting everyone else. This is a spirit that will go beyond the people of Israel and that will be shared by all people across the world, because all people have an intrinsic value and are not mere backdrops to the drama of the people of Israel. Only then will it truly be possible for the human being to live fully as a human being. And that is not only to be a moral person interpersonally but to realize one’s full potential of clinging to God, to His ways and to His light. Only an untiring drive to have a dynamic relationship with the Divine suffices, and even complete mitzvah observance without that is mere egocentrism that is incapable of bringing a messianic age. And only an untiring drive to selflessly give to others can help lead to that goal, because only in a relationship with other human beings, in which one continuously receives responses from others, can one see if one’s giving is authentic. If I may include in a review an excerpt of another review, Rabbi Aryeh Ben David (founder of Ayeka: Center for Soulful Education) writes, “If I were to recommend one book to commence the study of Kabbalah, it would be Aryeh Siegel’s Giving. This is not only an introduction to primary Kabbalistic ideas, but also a redirecting of how to live a life of Torah. With this scholarly and graceful translation, Aryeh Siegel offers us the opportunity to transform ourselves.” As said above, this is largely a book of an intense conceptual overview of the world and its dynamics. This book therefore has little discussion of many of the terms or ideas usually addressed in such books: the sefirot, and so forth. Is following the path this book recommends the way to attain the goals that this book proposes? I would say yes, if that way is congenial to you. However, one might argue, based on this book’s insistence on going against one’s natural inclinations, one should follow its path precisely if one finds that the way is not congenial—if it is not self-serving. But in my view, that way lies madness. This book may certainly stir up your brains and challenge you deeply. Should you then allow its ideas to seep into you and remain a Giving dilettante as you continue in other ways to be a good Jew (or human being) or seek two fellow-searchers to form a Giving mini-society? Can you end up, as an individual or as a member of a mini-Giving society, fooling yourself, growing more ego-inflated as you think that you are becoming a more rarefied, superior being—and to which teacher will you then go for correction? Is there a sort of Giving school, just as students preparing to be psychologists must undergo therapy and training? The answer is of course blowing in your spirit--or, I am reliably informed, in Telzstone at Rav Gottlieb's bet midrash (and, so long as the Covid-19 virus is "viral" - on the ברכת שלום youtube channel).

1 Comment

The Tzaddik Loves Everyone, Jew and Non-Jew: A Teaching of the Seminal Hasidic Work, Noam Elimelech12/9/2020 When the tzaddik prays on behalf of a sick person, and the like, his prayer is answered. Apparently, that indicates that the simple, true Creator is changing, heaven forbid. But the root idea is that Hashem created the letters, which are in potential with Him. The tzaddik combines these letters so that they will be read in accordance with his will—i.e., the tzaddik prays by means of combining the letters. And so there is no change in God, heaven forbid. The letters existed from the beginning, only that the tzaddik combines them. It is specifically the tzaddik who is answered in his prayer. As our Sages said, “A person who has a sick person in his house should go to the tzaddik and pray” (Bava Batra 116a). But why is that? Why shouldn’t every person pray and the letters will be combined? The answer is that the holy Torah was created with love. As the siddur states, “He Who chooses His nation of Israel with love.” The tzaddik also loves Hashem and every person in the world. As Rabbi Yochanan said, “No one ever greeted me first on the street, not even a gentile” (Berachot 17a). But that is not the trait of every person. Therefore, the letters only combine for the tzaddik who loves all. And thus “Yaakov sent angelic messengers,” these being letters and words. He sent them “to Esav his brother,” meaning that even Esav was complete with him as his brother. Noam Elimelech: Parashat Vayishlach  Hasidism introduced or, at least, strengthened the concept of story-telling as an act of holiness and transformation. “People say that stories are good for putting people to sleep,” stated Rabbi Nachman of Breslov, “But I say that stories are good for waking people up.” One such type of story is that of a visitation by Elijah the prophet—Eliyahu Hanavi. The most worthy person recognizes Elijah and is taught by him. More commonly, Elijah appears to people as an anonymous figure who brings about a miraculous change in their lives. And so many times a mysterious and beneficent visitor is assumed to be Elijah. Eliezer Shore’s Meeting Elijah: True Tales of Eliyahu Hanavi contains stories that he was told (or was involved in) that include serendipitous meetings with such figures, whether they are fortunate or even miraculous, as well as stories in which an ordinary person—including the narrator himself—finds himself playing the role of Elijah. In our era, we are swamped by news, information and misinformation that is sometimes trivial and often negative, triggering our anger, paranoia, and disconnecting us from a higher, spiritual view of reality. It is what is called mochin dekatnut—“a constricted state of consciousness.” The opposite of that is mochin degadlut—“an expanded state of consciousness.” Sometimes a way to reach that state is to sit and study a passage of Tzidkat Hatzaddik. And sometimes a way to reach that state is to rise above a world of pettiness, anger and meaningless by reading a story. I really enjoyed Meeting Elijah. Its short stories are invigorating capsules of uplift and a gaze at a higher plane of reality existing even within our plane of reality. Here is one of its 57 charming stories: The Ride to the Kotel About ten years ago, I was studying at the Har HaMor yeshivah, in the Kiryat Yovel neighborhood of Jerusalem. I was single and had been dating for a couple of years. It was a frustrating period. Finally, I met Ayelet, a sweet, sensitive and beautiful young woman. We dated for several months, and everything seemed to be moving smoothly toward an engagement. We had a wonderful relationship, and I can honestly say that I wanted to marry her. Suddenly, however, she decided to call it all off. She explained, apologetically, that it was just not what she was looking for. I was heartbroken. Though I tried to take the rejection as best as I could, a deep pain lingered inside me. When, one night, several months later, I heard that Ayelet had become engaged, I was devastated. All the pain and disappointment that I had bottled up came flooding out. I felt alone and abandoned. I wanted to cry, to hug someone. But there was no one in the yeshivah who could really comfort me, and my family lived far away. What does a yeshivah student in Jerusalem do when faced with such a dilemma? There’s only one place to go—the Kotel! I decided to go to the Western Wall and pour out my heart to Hashem, asking Him for comfort and His spiritual embrace. I left the yeshivah at about 11:30 at night, hoping to catch one of the last buses to the Western Wall. As I waited at the bus stop, I turned my eyes and heart toward Heaven, looking beyond the stars to a Presence that I knew would help me. At that very moment, a motorcycle pulled up beside the bus stop. A heavyset man with a full beard and bright blue eyes lifted his visor and smiled at me. “Where’re you going?” he said. “Can I offer you a lift?” “I’m going to the Kotel,” I replied. “Perfect,” he said. “I’m going to the Old City. Hop on the back and hold on.” I climbed onto the motorcycle and put my arms around him, as he set off down the quiet Jerusalem streets. I hadn’t ridden many motorcycles in my life, and I felt a bit insecure, especially when the bike tilted and turned down Jerusalem’s winding alleys. I held on to the driver tightly, which created a somewhat awkward situation. I had never met the man before and didn’t even know his name, yet here I was sitting behind him, virtually hugging his broad back when I needed precisely that—someone to hug! I had a hard time not burying my face in his jacket and releasing my tears. By the time we reached the Old City, I felt surprisingly better, as though my pain had already been assuaged. The man dropped me off in the Jewish Quarter. I thanked him profusely and made my way down to the Western Wall. Don’t ask me how, but I sensed that my prayers had been answered even before I got there. About an hour later, I took a taxi back to yeshivah. Time passed, my heart healed, and about two years later, I met Eliana. Today, we are married and have two children, and we are very happy. But if you ask me whether the stranger on the motorcycle was Eliyahu Hanavi, I would have to say that he was not. His name was Menashe Ankori, and I now know him very well. After I married Eliana, he turned out to be… my father-in-law! * * * Heard from Gadi B. Rabbi Dr. Eliezer Shore is a teacher, writer and storyteller on topics of Jewish thought and spirituality. He teaches at various colleges and institutions around Israel and his articles and stories have appeared in journals and anthologies worldwide. He lives in Jerusalem. You may purchase Meeting Elijah book on Amazon. Various Thoughts of the Past Week

Having listened to some youtube videos describing various people’s “spiritual experiences,” I have been led to think that it is possible that one cannot say that the Jewish people have the most spiritual experiences, because other people of various faiths or of no faith have reported marvellous experiences. However, I think it is fair to say that the Jewish people have the most Jewish spiritual experiences. Where do we see in Jewish teachings brought to the ordinary person practices that lead or may be meant to lead to intense spiritual experiences? I think that the answer is Breslov Hasidism. In the modern understanding, there is a concept of spiritually intense experiences that are not “pure” but mixed with misunderstandings: spiritual emergencies, spiritual experiences with psychotic elements, delusional “insights” including grandiosity, etc. There is now an emerging field of transpersonal therapists who help a person going through such an experience to weather it and understand it properly. Are there such teachers in Breslov? (If you know the answer, please share them!) Are there other schools besides Breslov that help lift a person out of “ordinary” reality? Having marvelous psychedelic experiences is not a stated value in Torah. (Having marvelous delicatessen experiences can be.) Rav Kook expressed his feeling that descending from higher realms to the confines of halachah was challenging and painful. Nevertheless, it was something necessary. One might speculate that one of the purposes of halachah and Gemara is precisely to deal with people who have a tendency to be so spiritual that they are not in contact with this world and to ground them. One might go even farther and speculate that this is one aspect of the function of those parts of the Torah that are morally difficult. That really grounds a person. The Torah does an excellent job, then, in grounding a person. But too much grounding creates its own problem, because it then is boring to the person who is seeking something deeper or something more experiential. In sum, I think it is fair to say that the Jewish people have the most Jewish spiritual experiences. The texts of Jewish spiritual experience, to the extent that I am familiar with them, blend spirituality with so much wholesomeness, groundedness and “orthodoxy” that they are safe and lead to a life of true spiritual and moral well-being and value. The side-effect is of course that the person who wishes for something to touch him on what he feels is a deep level can find it hard to find that. Apropos of that, generally I have seen that the “fear” of God is described as fitting into either of two categories: the lower fear of God, which is the fear of being punished for one’s sins, and the higher fear of God, which is a sense of awe in His presence. What about a blend of these? In other words, a person could feel that he is in the presence of an Entity so powerful and pure that just naturally in the presence of that Entity he will be toran apart and cease to exist, in modern parlance that he will suffer an ego-death. So I propose that we go out and do what we can do better than any non-Jew can do, which is to be Jewish. From Polish Hasidism to Scottish Literature and When Might a Person Think that a Sin is Not a Sin?10/21/2020 The Hasidic sefer Mei Hashiloach is particularly famous for its passages describing how biblical figures struggled with taking action that apparently or actually transgressed halachah. One of the factors involved is their sense that they are on an unalterably high level, such that the action they wish to take must indeed be the fulfillment of what God wants of them.

Thus: Do not imagine, heaven forbid, that Zimri [who publicly had relations with the Midianite princess, in consequence of which Pinchas killed them both] was licentious, heaven forbid, because the Holy One, blessed be He, would not make a parshah in the Torah regarding a licentious person. But there is a secret in the matter. There are ten levels in lewd behavior. The first level is a person who adorns himself and proceeds purposefully to commit a sin—i.e., he himself draws his evil inclination onto himself. And following that there are another nine levels. And on each level when a person’s power of choice is taken away from him he cannot save himself from sin, until the tenth level—i.e., a person who removes himself from the evil inclination and guards himself from sin with all his might until he cannot guard himself any more against it. and then, when his evil inclination overcomes him and he commits the act, then that is certainly the will of Hashem, and as with Judah and Tamar, for she was truly his marital partner. And that is what was here: for Zimri in truth guarded himself from all evil lusts, and now he had the idea that [the Midianite princess] is his [marital] partner, since he lacks the power to remove himself from that act. And Pinchas said, on the contrary, that he still has the power to remove himself from that…. Mei Hashiloach: Parashat Pinchas Now we move 2500 kilometers west, from Izbica, Poland, to Edinburgh, Scotland, where the writer James Hogg lived. The following information is gleaned from Mr. Hyde & the Epidemiology of Evil by Theodore Dalrymple, which appeared in The New Criterion (September 2004). In 1824, James Hogg published anonymously The Private Memoirs and Confessions of a Justified Sinner. In this book, the protagonist, Robert Wringhim, is persuaded by his father, a Calvinist churchman, that he is one of the saved, according to the Calvinist doctrine of predestination. This is very different from what the Mei Hashiloach is discussing, which is a person who comes to a state of sinlessness due to his own prodigious efforts. Nevertheless, both Wringham and (lehavdil [?]), Zimri, share the view that, being faultless, their actions must so be as well. Wringham, unlike the Mei Hashiloach, does not countenance the idea that such a state must be possible, and so it is the devil who tells Wringham that whatever he does must be definition be the right thing to do. Despite the differences between the Mei Hashiloach and James Hogg, it is intriguing that there is this shared interest in this theme by two men who, although contemporaries, might be thought to be living on two different planets in terms of their environment, influences, outlook, and spiritual station. In many places, the Mei Hashiloach places many conditions on any human being aspiring to being like Judah and being able to know that his seeming desire to act in a non-halachic manner—so many conditions, in fact, that practically speaking no one is capable of attaining that level. People have therefore been puzzled as to why he posited this theoretical model in the first place. Perhaps (as indicated in his disciple’s Tzidkat Hatzaddik) it is to offer comfort in retrospect to those who look back upon their actions and reflect that despite their greatest efforts they fell: to tell them that on some level they were walking upon a path that had been immutably set forth for them. That attitude itself can make it possible for a person to acknowledge what he has done and thus take responsibility for it and engage in a more genuine teshuvah. Apropos of making available my translation of Hitbodedut Meditation by Rabbi Avraham, son of the Rambam, it would be valuable to analyze people's actual practice of hitbodedut a la Rabbi Nachman of Breslov. It would make a wonderful graduate study.

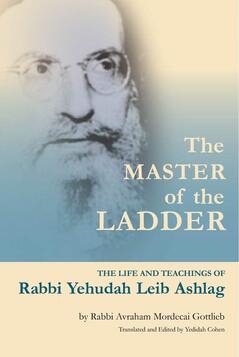

Some sample questions could be: The details of people's hitbodedut: How many times a week? How long each time? How many times a day? The place. The time. The nature of the hitbodedut: speaking, singing, screaming, crying, dancing, clapping. How long has one been doing it? How many women and how many men do hitbodedut? What has the person prayed for? Has he [or she, and so for the rest of the text] prayed for things and gotten them, or prayed for things and not gotten them? And then, the more interesting questions. How has it affected a person's life? Has it made him more spiritual? Has it made him closer to God? Has it made him more intelligent? Has it improved his character traits: is he less angry, more kind, a better parent? Conversely, has he seen any negative effects: If he has prayed and not received what he wanted, has he grown bitter? Has the fact that he does hitbodedut made him feel better than others? Has it created or exacerbated personal, spiritual or character problems? How has the experience of hitbodedut changed over the years? What has his purpose been in doing hitbodedut? Has hitbodedut done what he expected it to do or more, or less? How does his hitbodedut experience compare with other forms of spiritual work, whether Jewish or non-Jewish? I would be very interested to hear about people's experiences and perhaps share them with others (of course preserving confidences when requested). You can click "contact me" at the right of this blog post to get in touch. I look forward to hearing from you.  Rabbi Yehudah Leib Ashlag (1885-1954) was the author of the famed commentary on the Zohar called Hasulam (The Ladder). The Master of the Ladder: The Life and Teachings of Rabbi Yehudah Leib Ashlag (by Rabbi Avraham Mordecai Gottlieb, translated and edited by Yedidah Cohen) is a presentation of Rabbi Ashlag’s life and teachings. The book may be described not so much a full-fledged biography as a series of anecdotes stretched across a chronological framework. These are interspersed with sections in which the author, himself a leading student of the teachings of Rabbi Ashlag, offers his own presentations of Rabbi Ashlag’s thought. Throughout the book the figure of Rabbi Ashlag appears as an intense and holy man, and the stories have an intensity and purifying quality, verifying the Hasidic teachings that stories of tzaddikim are in themselves a powerful means of transmission of Torah and holiness. The book begins with a particularly powerful spiritual testimony: Rabbi Ashlag’s own writing on how he experienced an encounter with his own teacher, the Belzer Rebbe (Rabbi Yissachar Dov Rokeach) in 1919. Interestingly, this document was one of a number of pages that Rabbi Ashlag wished to consign to the flames but which were fortunately saved. In this document, Rabbi Ashlag describes how he was immersed in a state of elevated consciousness that he calls the Light of Wisdom. He comes to the Belzer Rebbe for guidance, and the entire encounter is conducted in an indirect manner of inference and implication. Rabbi Ashlag is in a state of consternation because apparently the Belzer Rebbe wishes him to descend from this state of consciousness in order to operate on the level of a state of consciousness called the Light of Lovingkindness. With misgivings, Rabbi Ashlag accepts this directive, and that new approach marks the direction of the remainder of his life. This brief autobiographical document—which is presented twice: once in itself and once with a detailed commentary and explanation—is an extraordinary description in which Rabbi Ashlag describes his own powerful emotions, ranging from distress to delight, his relationship with the Belzer Rebbe—his questioning the Belzer Rebbe and his shame at doing so—and his sense that the this-worldly aspect of this encounter was only a part of a broader reality. Rabbi Ashlag reveals his inner world and his bond with his students in his letters, in which he tells of a master kabbalist whom he learned from and offers his students counsel and guidance. One letter is particularly revealing of his deep concern for his students, and that letter too is presented with a commentary. He gathered a group of dedicated students around him, and under his direction they formed a spiritual society, learning from him throughout the night with great personal sacrifice—a society similar to others, such as that around the Ramchal and that described by the Piaseszner Rebbe. In 1921, Rabbi Ashlag told his wife, “I have nothing more to do in this world. I have already rectified that which was laid on me to rectify.” In order to remain alive, he and his family moved from Warsaw to the Land of Israel, where he spent the rest of his life (with a couple of exceptions, such as a few years’ stay in London). Rabbi Ashlag’s great mission in life was to present the teachings of the Ari in language that would be clear and accessible. Prior to writing his magnum opus, the Sulam, he wrote voluminously directly on the cryptic teachings of the Ari. However, Rabbi Ashlag’s intent was not to make Kabbalah accessible to one and all, religious and non-religious, but to make it accessible to those who are committed to the path of the Torah. Thus, when a review of his book on the teachings of the Ari was published in a Warsaw newspaper, he was deeply shocked, states Rabbi Gottlieb. “Copies of the manuscript of the Panim Meirot Umasbirot were sent to Poland. Somehow, one fell into the hands of one Hillel Tzeitlin, a Jew, who, originally from a Chasidic background, had renounced his upbringing and become involved in the ideas of western philosophy. Tzeitlin published an article in the Jewish newspaper, Der Moment, praising the innovative work of the holy Sage. But when Rabbi Ashlag learned that his work had fallen into the hand of Tzeitlin he was deeply shocked. Praise from such a man would only arouse opposition to his work in the orthodox circles in Warsaw.” I quote this passage at length because it is puzzling. The author’s disparaging reference to Tzeitlin—“one Hillel Tzeitlin, a Jew”—indicates that he is unaware that Tzeitlin, after renouncing his Chasidic background, returned to the observance of the Torah and to publicizing its spiritual treasures among the non-religious intellectual classes of Warsaw. It is also puzzling that Rabbi Ashlag would have been so upset that Hillel Tzeitlin’s article might lead the “orthodox” to dismiss his work, when he himself encountered so much opposition and denunciation of his innovative work in Jerusalem from the traditional Sephardic kabbalists and from the “old yishuv” Orthodox community. (A second edition of this book would do well to rectify this description of Hillel Tzeitlin and clarify Rabbi Ashlag’s concerns. Incidentally, in this first edition of the book, the word “page” is deleted wherever it should appear. This too could be corrected in a second edition.) It is clear from the many comments quoted in this book of Rabbi Ashlag’s relatives and students, and from the many narratives, that Rabbi Ashlag was a rare and holy individual who lived on a plane different than the plane on which ordinary mortals live. Reading this book offers the ability to experience something—at least an echo or a reflection—of that holy, the ability to glimpse a reality beyond that of the every day, and the opening of the heart to yearn for that reality. Order Master of the Ladder from Nehora Press or from Amazon. |

Author

Yaacov David Shulman is the author, translator and editor of fifty books of Jewish spiritual and literary meaning. Archives

January 2021

Categories

|

RSS Feed

RSS Feed